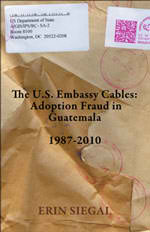

As an adoptive mother to two children born in Guatemala, as well as the author of a memoir about Guatemalan adoption, I read every book, article, and blog post I can find on the subject. No single piece of writing has fascinated me more than The U.S. Embassy Cables: Adoption Fraud in Guatemala 1987-2010, by investigative reporter Erin Siegal. The publication isn’t a book in the traditional sense, but a 717-page compilation of “cables” (pre-internet communications), memos, and emails, generated by officials in the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala City and the U.S. Department of State (DOS). Siegal obtained the material from DOS after filing 30 Freedom of Information Act requests between November 2008 and 2010.

The book’s unconventional format takes some getting used to, but that’s precisely what makes it so compelling: the reader feels he is privy to something secret and private, a communication never intended to be revealed. Those readers who stick with the challenge are rewarded with a deeper understanding of one particular aspect of adoption between Guatemala and the United States—fraud–as it was reported via the keyboards of U.S. government officials.

Adoption between Guatemala and the United States was shut down in December 2007, due to allegations of corruption. The thousands of Embassy cables regarding corruption—what it entailed, how much there was, and who knew about it and when—both enlighten and disturb.

Concerns about falsified documents are stated as early as August 1987, as demonstrated by this memo generated by officials in the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala City: “[T]he ability of persons involved in child trafficking to proceed as if the adoption were completely legal is facilitated by the ease with which Guatemalan documents can be falsified.” (13) And from July 1993: “Just because the civil documents and identity cards presented are genuine, does not mean that the information contained in them is correct. Guatemalan civil documents, particularly birth certificates, containing false information are easily obtainable for a small fee.” (126)

A memo from 1989 sounded this alarm: “Attorneys who do adoptions in Guatemala receive fees that are astronomical by local standards. One adoption attorney regularly charges the adoptive parents 12,000 dollars, plus 150 dollars per month for childcare… (Most heads of family in Guatemala make less than 150 dollars per month… Judges of the family courts make about 500 dollars per month, and social workers make about 200 dollars.) The incentives for fraud are very strong…(34).”

Indeed, for some unscrupulous attorneys, the incentives were irresistible, as demonstrated by this 1991 memo: “Since we began routine interviewing of birth mothers one year ago, we have detected cases of baby selling (for very modest sums), imposter mothers, presentation of false birth certificates, children not meeting the legal definition of orphan and deception of birth mothers as to the legal consequences of adoption by local attorneys. We detect this type of obvious irregularity in about 5 percent of the cases presented.” (93)

No follow-up memo is published to interpret this data, so readers are left to wonder if “obvious irregularity in about 5 percent of the cases” is expected and normal, or considered off-the-charts. Nor do we learn if this number remains constant or changes over time. In any case, a quick mathematical calculation determines that this note was written 21 years ago, 16 years before any concerted efforts were made to reform the system.

With memo after memo detailing questionable paperwork coupled with more and more money, readers may dread turning the page, fearing the situation will turn violent. And then it does. This communication dates from September 1998: “Post was contacted by Guatemalan national, [blank], who claimed that his daughter was given up for adoption to an American couple without his knowledge and consent… Mr. [blank] was murdered shortly after he was interviewed by a consular officer regarding the case.” (377)

Even DNA tests, which the Embassy instituted on a wide scale in 1998 after repeated requests to DOS, were not failsafe. Memos state that a DNA match between relinquishing mother and her child did not discount coercion of the mother. Moreover, adoption attorneys, facilitators, and other interested parties were often present when doctors took DNA samples, nullifying the sample’s integrity.

The adoption story told by The Embassy Cables cannot be regarded as complete or balanced because the subject is too complex to be summarized by 717 pages of memos that lack interpretation, reflection, or context. Nevertheless, as a historical record of the U.S. government’s statements and actions regarding adoption as it was practiced between 1987 and 2010, The Embassy Cables makes a singular contribution.

The Embassy Cables: Adoption Fraud in Guatemala 1987-2010 is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and independent bookstores. Some readers report that the downloaded version requires a magnifying glass to read. For more information, visit Erin Siegal’s website, erinsiegal.com.

This review was cross-posted at Adoption Under One Roof.

Image Credit: Cathexis Press

Tags: adoption fraud, book reviews by Jessica O'Dwyer, corruption in adoption, Erin Siegal, Guatemalan adoption, Guatemalan adoption and corruption, intercountry adoption, international adoption, The Embassy Cables, The Embassy Cables by Erin Siegal, The U.S. Embassy Cables, The U.S. Embassy Cables: Adoption Fraud in Guatemala 1987-2010 by Erin Siegal, U.S. Department of State and Guatemalan adoption

ShareThis

ShareThis

Hello Jessica,

Thank you for your review of this book. I was not aware of it. My son’s adoption was completed in Guatemala in 2005.

It’s difficult to believe that there could have been “widespread” corruption in the system in the mid 2000s. DNA tests confirming that the birth mother was the mother of the child, and social worker interviews asking if there was coercion were in place at that time.

The statement (from the book, I assume) “adoption attorneys, facilitators, and other interested parties were often present when doctors took DNA samples, nullifying the sample’s integrity” seems very strange to me. How can an attorney being present effect results of a DNA test? Perhaps the facilitators/attorneys were present because the DNA test process was a hardship and confusing for many birth mothers who may have to travel to a lab in a far off city for the test.

But thank you for the review!

I searched for information about this book, and I’m getting kind of skeptical. The publisher listed for both of this author’s books, Cathexis Press, is not a publisher as far as I can see. The only books Cathexis Press has published are these two books by Erin Siegal. That sounds like vanity press to me, which makes the books themselves somewhat unreliable or at least open to scrutiny.

The U.S. Cables “book” I would not even call a “book” at all. It is only sold through Amazon as an Amazon Digital Edition. It is not held by ANY library, it is not available from any books seller other than Amazon. Definitely vanity press (meaning the author likely paid to have it “published”).

Hi Deborah:

Thanks for writing.

According to Embassy memos, corruption was detected in about 5 percent of cases. Whether that is a lot or a little, I don’t know. Nor do I know whether that number remained constant. What I do know is that corruption is widespread throughout many layers of Guatemalan bureaucracy, as has been documented by independent organizations such as CICIG and is reported almost daily by Guatemalan and international news outlets.

I, however, am a person who believes in degrees of corruption–that is, a falsified document is different from a birth mother who was coerced. Why? Because in Guatemala and many other countries around the world, falsified documents are common and often necessary for survival. In Guatemala, many people from surrounding countries such as Honduras operate with false cedulas or identity cards. Why? Because as dangerous as Guatemala is and as depressed its economy, Guatemala is less dangerous and economically depressed than Honduras. Similarly, in the USA, tens of thousands of Guatemalans are living and working while undocumented–a form of identity falsification. I think most people would agree that’s an order of magnitude “less bad” than snatching a baby from someone unwilling to give him up.

Do I think it’s “right” that adoption documents may have been falsified–fake names and addresses, fake marital status. Of course not. But viewed within the context of the country, I’m not suprised by it.

Re: the DNA. A DNA test is taken by swabbing the inside of the mouth to collect cells from the cheeks of a birth mother and her baby. Each of the two cotton swabs is sealed into plastic bags, and sent to a lab in North Carolina for analysis. One easy way this can be corrupted by an attorney or other interested party: By swapping the swabs. In other words, attorney holds swab from the actual birth mother or baby in his pocket, and switches it with the sample taken in the room. Why would someone do this? One reason, among many possible: Because if a birth mother relinquishes multiple babies, a red flag goes up. A “fake” birth mother goes in for the test, but the sample is from the actual birth mother, and thus is a match.

Does this happen often? I doubt it. Most attorneys and facilitators wanted to process “clean” adoptions. They didn’t want to raise red flags. They didn’t want trouble. But if someone had wanted to compromise a DNA test, they could have.

What concerned Embassy officials more that falsified DNA tests was coercion: the fact that maybe a birth mother was unsure if she wanted to relinquish or had second thoughts. A DNA test couldn’t measure degree of free will, which is why the Embassy often also conducted interviews.

As for Erin Siegal’s publishing credentials: Yes, from what I can determine, Cathexis Press is owned and operated by Erin Siegal. However, the text of The Embassy Cables is taken from actual Embassy communications, reprinted and published by Erin Siegal. The reason I read and reviewed the book is that it contains primary source material– memos and transcripts and emails–which I hoped would shed light on the history of adoption in Guatemala, and deepen understanding of it. In that regard, the book, for me, was successful, although as you say, it’s not really a book at all, but a compendium.

When I bought The Embassy Cables, it was available in paperback for a very hefty sum–I believe ~ $50. Perhaps now it’s only available digitally. I don’t know.

After reading the Embassy Cables, I came away impressed with the safeguards our government put in place in their attempts to protect birth mothers, children, and American citizens. But I also realized, in a profound way, that a system can only be as honest as the people working within it. Reading the Embassy Cables, I got the feeling there was a percentage of people motivated, not by their love and concern for babies and children, but by greed. Tragically, these dishonest players corrupted an entire system, and ultimately shut it down.

As you probably know, I’m also an adoptive mother, to two children born in Guatemala. I remain a staunch supporter of adoption, and am close to despair that 200+ cases pending since 2007 are still in limbo. On bad days, I wonder if we as human beings are capable of ever establishing a transparent and honest adoption system, one that will protect children and birth mothers and adoptive families. On good days, I keep hoping.

Thank you again for writing.